The Profound World of Bitter Gourd Monk: Understanding Shitao’s Landscape Mastery

苦瓜和尚的深邃世界:理解石濤的山水畫境界

Prologue: The Monk Who Transformed Chinese Landscape Painting

序言:改變中國山水畫的僧人

Shitao (1642–c. 1707), known as the Bitter Gourd Monk, stands as one of the most revolutionary figures in Chinese art history. A Qing Dynasty painter and ultimate master of ink wash painting, his artistic legacy continues to captivate viewers centuries later with its profound spiritual depth and technical brilliance.

石濤(1642年–約1707年),號苦瓜和尚,是中國藝術史上最具革命性的人物之一。作為清代畫家和水墨畫的巔峰大師,他的藝術遺產以其深邃的精神內涵和精湛的技藝,在數世紀後依然吸引著觀賞者。

I. The Wandering Prince: A Life of Transformation

一、流浪王子:轉變的一生

Born Zhu Ruoji in 1642, Shitao was no ordinary artist. As a descendant of the Ming Dynasty’s Jingjiang Prince and son of Zhu Hengjia (the Yuanzong of the Southern Ming), he carried royal bloodline that became a burden following the Ming Dynasty’s collapse. Forced into Buddhist monastic life as a child after family tragedy, he adopted the dharma name Yuanji (原濟) or Yuanji (元濟), and later became known by his artistic names: Shitao (石濤), Bitter Gourd Monk (苦瓜和尚), Great Washer (大滌子), and Qingxiang Old Man (清湘陳人).

石濤本名朱若極,生於1642年,他並非普通藝術家。作為明代靖江王的後裔和南明元宗朱亨嘉之子,他身負皇室血統,這在明朝滅亡後成為負擔。童年遭遇家庭變故後被迫出家為僧,取法名原濟(或元濟),後來以他的藝術別號聞名:石濤、苦瓜和尚、大滌子、清湘陳人。

His life journey took him from Guangxi’s Quanzhou to eventually settling in Yangzhou during his later years. Decades of wandering as a itinerant monk supporting himself through painting profoundly influenced his artistic perspective, allowing him to absorb diverse regional landscapes and cultural influences.

他的人生旅程從廣西全州開始,最終晚年定居揚州。數十年作為雲遊僧人以賣畫為生的流浪生涯,深刻地影響了他的藝術視角,使他得以吸收多樣的地域景觀和文化影響。

II. Evolutionary Artistry: From Tradition to Revolution

二、演變的藝術:從傳統到革命

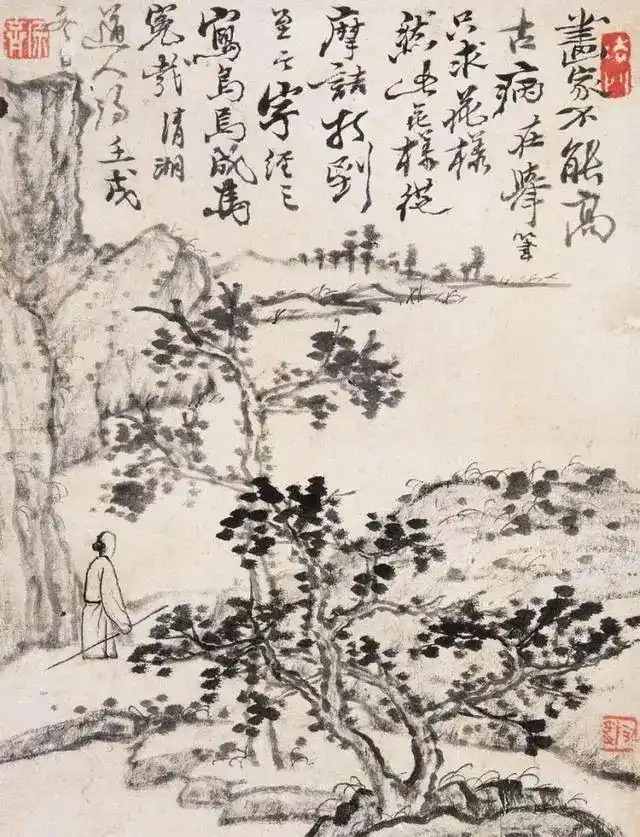

Early Period (1660s-1690s): Shitao’s early landscapes paid homage to Song and Yuan masters, characterized by sparse, elegant compositions and clear, bright execution. His style during this period demonstrated technical mastery while maintaining a certain classical restraint.

早期(1660年代-1690年代): 石濤的早期山水畫師法宋元名家,特點是疏秀的構圖和明潔的筆法。這一時期的風格展現了技術上的精通,同時保持了一定的古典克制。

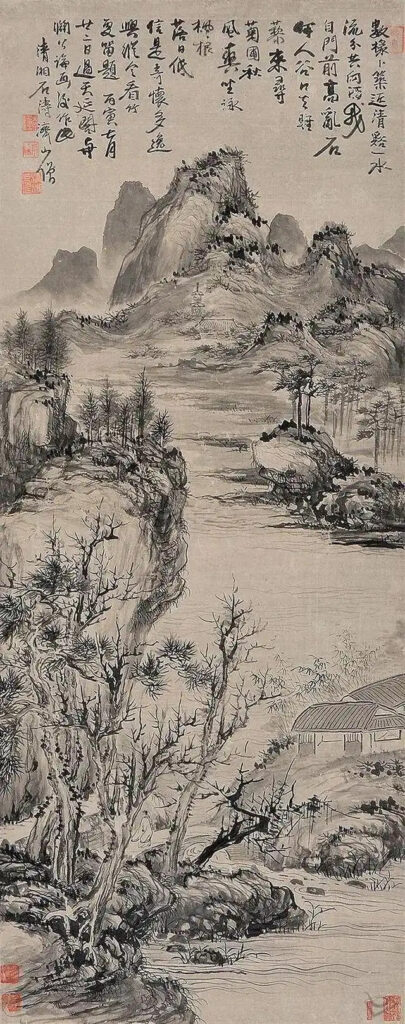

Late Period (1690s-1707): In his mature years, Shitao’s brushwork became dramatically unrestrained and expressive. His ink applications turned increasingly dramatic—sometimes dripping wet, sometimes dry and scratchy—creating compositions of extraordinary vitality and emotional depth. He particularly excelled at album leaf paintings (册頁 – cèyè), small format works that contain immense artistic vision.

晚期(1690年代-1707年): 在成熟期,石濤的筆法變得豪放不羈且極富表現力。他的墨法運用愈加戲劇化——時而淋漓濕潤,時而乾澀飛白——創造出充滿非凡生命力和情感深度的構圖。他尤其擅長冊頁小品,在方寸之間展現巨大的藝術視野。

III. Mastery Across Genres: Beyond Landscapes

三、多面才華:超越山水

While renowned for his landscapes(Chinese art), Shitao’s artistic genius extended across multiple genres:

雖然以山水畫聞名,石濤的藝術才華橫跨多個領域:

- Flower and Bird Paintings (花卉): His floral works exhibit a潇洒 (xiāosǎ – natural and unrestrained) elegance and隽朗 (jùn lǎng – meaningful brightness), radiating天真烂漫 (tiānzhēn lànmàn – innocent charm) and清气袭人 (qīngqì xí rén – refreshing purity that strikes the viewer).

- 花卉畫: 他的花卉作品展現出瀟灑的優雅和隽朗的氣質,洋溢著天真爛漫的魅力和清氣襲人的清新感。

- Figure Paintings (人物): Shitao’s figures display生拙 (shēng zhuō – raw simplicity) and古朴 (gǔpǔ – archaic elegance), creating a distinctive style that stood apart from his contemporaries.

- 人物畫: 石濤的人物畫呈現生拙和古樸的特點,創造了與同時代畫家截然不同的獨特風格。

- Calligraphy and Poetry (書法與詩文): A skilled calligrapher and poet, Shitao integrated the “Three Perfections” (三絕 – sān jué)—painting, poetry, and calligraphy—into cohesive artistic expressions.

- 書法與詩文: 作為嫻熟的書法家和詩人,石濤將「三絕」——畫、詩、書——融合為統一的藝術表現。

IV. Philosophical Foundations: The Theory Behind the Art

四、哲學基礎:藝術背後的理論

Shitao’s artistic practice was deeply informed by his philosophical insights, most notably expressed in his treatise “Kugua Heshang Hua Yulu” (《苦瓜和尚畫語錄》 – Comments on Painting by Bitter Gourd Monk). His most famous principle—”搜尽奇峰打草稿” (sōu jìn qí fēng dǎ cǎogǎo – gather all strange peaks to make sketches)—encouraged artists to absorb nature’s diversity before creating original works.

石濤的藝術實踐深受其哲學見解的影響,其中最顯著地表現在他的著作《苦瓜和尚畫語錄》中。他最著名的原則——「搜盡奇峰打草稿」——鼓勵藝術家在創作原創作品之前,先吸收自然的多樣性。

He advocated for “一画” (yī huà – One Stroke) theory, suggesting that all painting originates from a single, primordial brushstroke containing infinite creative potential. This concept connected painting to Daoist and Buddhist ideas of primordial unity.

他提倡「一畫」理論,認為所有繪畫都源自一筆包含無限創造潛能的原始筆觸。這一概念將繪畫與道家和佛教的原始統一觀念相聯繫。

V. Legacy and Masterworks: Enduring Influence

五、遺產與傑作:深遠的影響

Among Shitao’s extant masterpieces, several works particularly demonstrate his revolutionary approach:

在石濤現存的傑作中,有幾幅作品尤其展現了他的革命性手法:

- “搜尽奇峰打草稿图” (Gathering All Strange Peaks for Sketches): This monumental scroll embodies his approach to artistic creation, showing diverse mountain forms synthesized into a cohesive composition.

- 《搜盡奇峰打草稿圖》:這幅巨作手卷體現了他的藝術創作方法,展示了多樣的山峰形態被融合成統一的構圖。

- “山水清音图” (The Clear Sound of Mountains and Waters): Demonstrates his mastery of atmospheric perspective and emotional resonance through ink wash.

- 《山水清音圖》:展現了他通過水墨表現空氣透視和情感共鳴的精湛技藝。

- “竹石图” (Bamboo and Rocks): Exemplifies his ability to invest simple subjects with profound spiritual meaning.

- 《竹石圖》: exemplifies his ability to invest simple subjects with profound spiritual meaning.

Shitao’s influence extends far beyond his lifetime, inspiring generations of Chinese painters including the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou and modern masters like Zhang Daqian. His willingness to break from tradition while maintaining deep respect for classical principles created a bridge between past and future in Chinese art.

石濤的影響遠超其生前,激勵了包括揚州八怪和張大千等現代大師在內的數代中國畫家。他願意打破傳統同時又保持對古典原則的深刻尊重,在中國藝術中架起了過去與未來的橋樑。

VI. Viewing Shitao: A Guide for Modern Appreciation

六、欣賞石濤:現代鑑賞指南

For contemporary viewers, approaching Shitao’s works involves understanding several key aspects:

對於當代觀賞者,欣賞石濤的作品需要理解幾個關鍵方面:

- Embrace the Journey: Follow the artist’s visual journey through landscapes as pathways to meditation rather than literal representations.

- 擁抱旅程: 將藝術家在山水中的視覺旅程視為冥想路徑,而非 literal representations。

- Ink Appreciation: Notice how Shitao manipulated ink density, moisture, and brush pressure to create emotional texture.

- 品味墨韻: 注意石濤如何運用墨的濃淡、濕度和筆壓來創造情感質感。

- Empty Space: appreciate his masterful use of negative space (留白 – liúbái) as an active compositional element.

- 虛實相生: 欣賞他對空白(留白)作為主動構圖元素的精湛運用。

- Personal Response: Allow yourself an emotional response to his works rather than seeking purely intellectual understanding.

- 個人感受: 讓自己對他的作品產生情感回應,而非純粹追求理性理解。

Conclusion: The Eternal Wanderer’s Gift

結語:永恆流浪者的饋贈

Shitao’s art remains vital today because it speaks to universal human experiences: displacement and belonging, tradition and innovation, nature and spirit. His landscapes invite us to wander with him through mental and physical realms, discovering deeper meanings with each viewing. As the artist himself suggested, true understanding comes not from copying appearances but from capturing the essential spirit—a lesson that resonates across centuries and cultures.

石濤的藝術(Chinese art)至今依然充滿生命力,因為它訴說著普遍的人類經驗:流離與歸屬、傳統與創新、自然與精神。他的山水畫邀請我們與他一同在精神與物質領域中漫遊,每次觀賞都能發現更深層的意義。正如藝術家本人所提示的,真正的理解並非來自複製表象,而是捕捉精神内核——這一教訓跨越了世紀和文化,依然引起共鳴。

From 苦瓜和尚石涛的山水画,越看意境越深远!